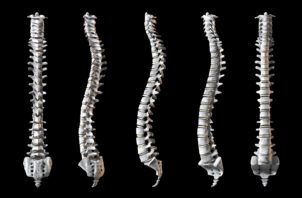

The human spine has an incredible ability to support, move, inform and nourish the body. It acts as the integrating factor between the upper and lower halves of the body and it supports the weight of the head, limbs and organs. Protected within the spine’s bony structure lies the spinal cord; a key element of the body’s neural network. Around the spinal cord we find the dural tube, a conduit for the “fluid” body. To function at its best, the spine must be stable, mobile and balanced. Too often though, we focus on “back strength,” with little attention to whether the deep musculature has the STAMINA to support the strength and power we lay over top of it.

The human spine has an incredible ability to support, move, inform and nourish the body. It acts as the integrating factor between the upper and lower halves of the body and it supports the weight of the head, limbs and organs. Protected within the spine’s bony structure lies the spinal cord; a key element of the body’s neural network. Around the spinal cord we find the dural tube, a conduit for the “fluid” body. To function at its best, the spine must be stable, mobile and balanced. Too often though, we focus on “back strength,” with little attention to whether the deep musculature has the STAMINA to support the strength and power we lay over top of it.

In movement training, when we look at methods for supporting and mobilizing the spine, we would do well to take the spine’s many and varied roles into consideration. Most often, a functional approach gets first view. Are the multifidi and other local stabilizers recruited well and consistently enough to stabilize individual vertebral segments in relation to load and range of motion? Are the spinal curves balanced? Can the spine articulate segmentally? Can it work as an integrated unit? In a clinical or traditional fitness setting, what I see most often are strategies to brace the spine in a stable position (e.g. plank), or to articulate spinal segments individually. But what about stamina and endurance for those muscles while the body is moving? Those smaller, deeper muscles are harder to FEEL working than the big, locomotor muscles. So usually we push through, working the larger movement, without really knowing whether we’re supporting ourselves well at all.

How do we figure out whether we have adequate support or not?

1. Try recruiting some of those deep back stabilizers in sitting/standing positions, or on all fours. Imagine a little pair of hooks connected to either side of the spine down close to the pelvis. Now picture a little string, (no more than a filament really), attached to each one of those hooks and ascending gently up the sides of the spine, floating past the back of your head. Imagine a gentle pull upward on those filaments, suspending your spine vertically.

You may or may not feel the engagement of the deep support. More likely, you will feel the ease that occurs in your movement as a result of recruiting those structures. For some that may feel like the low back widens and the legs relax, for others, that may mean the shoulders can hang, or perhaps the head feels lighter. It may be easier to lift an arm or a leg when you’ve got that sense of suspension going on in the spine.

2. Once you have a sense of connecting to that support in a static position, begin to play with movement. Lift one arm at a time. Can you maintain that sense of vertical ease in the spine? Let go of the “length” you feel, and lift a leg. Notice how it feels. Then add the supporting length in your spine again as you lift the same leg a second time. Does this leg lift feel different? Maybe easier?

3. As you begin to find that deep spinal support, play with ways you can support it with larger, more complex movements. Look for a quality of buoyancy and ease in your body. Keep your spine gently lengthening vertically as you move. For some, that may feel like a quality of effervescence, like champagne bubbles rising in a glass. Others may experience the feeling of hanging from a string, or stretching out like a snake. It doesn’t need to feel like you’re pulling or forcing your spine into length. It’s light and easy. Notice what happens when you engage the abdominal muscles at the same time. If engaging your abdominal muscles inhibits your sense of length, or makes you feel like you’re bearing down, you may need some education about how the core muscles integrate to create stability and mobility for the spine and thorax.

The idea is to make sure that no matter what you are doing; sitting at your desk, playing soccer, rock climbing or lifting weights, you have the endurance in those deep spinal muscles to support the integrity of the whole spine. It’s about deep low effort support for long periods of time. It’s about finding images that help you create lightness and ease, whatever your level of effort.

How do you know if it’s NOT working?

1. You’ll begin to feel compressed & heavier. You’ll feel as though you have to “bear down” to find your strength. Your limbs will feel like they weigh more.

2. More than just fatigue, your body will expend more effort to complete whatever task you are engaging in. Over time, this feeling will increase, and your movement will become less coordinated and more effortful.

3. You’ll create a muscular density and bulk that may result in reduced range of motion.

Want more? Here’s a little added bonus:

All the stuff we’ve talked about so far is pretty linear, clinical information. Try it and play with it. It works! But I still get a sense that this linear approach leads to a fairly passive role for the spine; with the action of the structures around it taking precedence. That’s fine, as far as it goes. But let’s consider this – can the spine have a life of it’s own? I’d like to offer the thoughts of one of my favourite teachers, veteran modern dancer and choreographer, Marc Boivin, from Montreal, Quebec:

“The spine to coccyx line can be perceived as a fifth limb (like the fifth limb of the starfish integrated within the spine and behind the bellybutton). Listening with perseverance to the dance between the head and the coccyx as an initiation for movement is also a great way to learn about our strategies of movement. We often choose to contract a part of this dynamic opposition in order to push against another body part; this then closes a part of the body and inhibits the movement from travelling totally through us.”

“The spine to coccyx line can be perceived as a fifth limb (like the fifth limb of the starfish integrated within the spine and behind the bellybutton). Listening with perseverance to the dance between the head and the coccyx as an initiation for movement is also a great way to learn about our strategies of movement. We often choose to contract a part of this dynamic opposition in order to push against another body part; this then closes a part of the body and inhibits the movement from travelling totally through us.”

When we perceive the spine this way, it’s not just a complicated series of joints that need stabilizing and mobilizing. Instead, it is an active and independent structure that can move and be moved to enhance the quality of our movement overall. And it reinforces the idea that every movement is a whole body movement.

If you’re new to all this, start with the purely functional. Explore how you can support your spine easily in static positions, under load and then adding more motion and more variety. Challenge yourself to develop the endurance you need to support yourself well over time and under varying load demands.

Once that feels comfortable, move beyond the merely functional and explore the spine’s capacity to act like a 5th limb. Maybe it seems a bit esoteric or woo-woo, but I promise you, it will open up a multitude of new possibilities for movement. When the spine comes alive, it infuses a new vitality into our whole bodies. That spring in your step you thought you’d lost? Find your spine and you’ll discover a buoyancy and lightness in your joints that will help you feel 10 years younger. What have you got to lose? A healthy, living, breathing spine can be a sublime experience!