We’ve all done it. You’re walking along, minding your own business, when you take a step and suddenly your ankle twists underneath you. Sometimes it just causes a hitch in your step. Sometimes the ligaments in the ankle joint get strained, causing pain and swelling. And without appropriate training to build structural support, once those ligaments are over-stretched or damaged… it’s much easier to “go-over” on that ankle again and again. So what can you do?

We’ve all done it. You’re walking along, minding your own business, when you take a step and suddenly your ankle twists underneath you. Sometimes it just causes a hitch in your step. Sometimes the ligaments in the ankle joint get strained, causing pain and swelling. And without appropriate training to build structural support, once those ligaments are over-stretched or damaged… it’s much easier to “go-over” on that ankle again and again. So what can you do?

You could look at this problem from a number of different angles, but major issue is likely inadequate stability in the ankle joint itself. The ankle joint needs to be mobile in order for you to adapt to the varied terrain on which you walk, run, hop, skip, jump and play. But it also needs to be “stiff” at appropriate moments. The way our overall structure “rests” on the ankle joint is important. To understand why, let’s look at the structure of the joint itself.

The efficient transfer of weight from legs to feet hinges quite literally on a bone called the “talus.” The talus articulates quite literally with your tibia and fibula (lower leg bones) above, and with your heel bone and other bones in the mid-foot below it. The talus acts simultaneously as a hinge joint with your lower leg bones, and as a keystone for the longitudinal arch of your foot. Interestingly though, even with its dual functions and responsibilities, the talus has no muscles attached to it! Instead, it is supported by ligaments, and moved and supported by the structures around it. Weight descending from above must be placed properly on a well-aligned talus. From there, the muscles of the lower legs which have attachments on the bottoms of the feet, and the muscles in the arches of the feet themselves can participate as needed fro stability and propulsion. When you see it that way, a pretty good case can be made for the importance of a balanced structure surrounding that ankle bone!

One of these balancing structures is a muscular “sling” which guides weight from your lower leg onto the talus, helps to support the arches of the feet, and participates in plantar flexion or “pointing” the foot. Think of it a little like a stirrup under foot, which attaches higher up on the calf. The outside part of the sling is made up of a muscle called the peroneus longus, which attaches on the upper outside edge of your fibula, just below the side of the knee. It travels down the outside of your lower leg, under the outside ankle bone, under and across the sole of the foot. With its journey from outside to inside, your peroneus longus connects both the outside, (weight bearing), and the inside (propulsion) parts of the feet to the lateral sides of the body.

The inner component of this sling is made up of the tibialis posterior muscle. The deepest muscle in your calf, it arises from the upper back of the shafts of the bones in your lower legs, and drops down the inner back of your leg, taking a little jog under the inside ankle bone to insert on bones on the inside of your mid-foot, and onto the 2-4th metatarsal bones.

The inner component of this sling is made up of the tibialis posterior muscle. The deepest muscle in your calf, it arises from the upper back of the shafts of the bones in your lower legs, and drops down the inner back of your leg, taking a little jog under the inside ankle bone to insert on bones on the inside of your mid-foot, and onto the 2-4th metatarsal bones.

Great. Now you know about the sling. The stirrup. What the heck are you supposed to do with it? How do you use it? Let’s start by talking about how this sling helps to stabilize the ankle in what is called “plantar flexion.” Plantar flexion is essentiallyl the action of pointing your foot. If you’re standing on your feet, it relates to the push off phase of your walk. When you rise up on your toes, maybe even in a pair of high heeled shoes, that’s plantar flexion.

You may notice that the ends of your tibia and fibula are fixed around your talus like a pair of pincers. Due to the shape of the bones, when you move into plantar flexion, the skinniest part of the talus moves into those pincers; meaning that the ankle joint will be a little unstable in this range. The ankle is comparatively stable in dorsi flexion (with toes pulled up towards your ankle), since that movement causes the widest part of the talus to move into the pincer. But just because the bony structure of the joint is inherently more unstable in plantar flexion, does that mean that all hope is lost? No. It just means that you have to pay a little more attention to creating stable support.

Heel raises are sometimes introduced as a way to sort this out, but the calf muscles themselves attach only on the heel bone – so they can’t really help here either. Strong calf muscles are important, but not the key to improving ankle stability. With focus only on the calf, the ankle is still vulnerable to lateral strains and sprains. Sometimes, loaded inversion & eversion exercises are recommended to address this. These are important for strengthening isolated muscles, but they don’t do a lot for educating your system about how to support and move the long lever of the body over the feet. But when this sling focus is added, ankle stability in plantar flexion is dramatically increased. The sling actively modifies the shape of the pincer – tightening its two sides and effectively solidifying its hold on the talus in plantar flexion. And with their attachments on the bottom of the foot, the sling muscles also tend to support the smaller bones of the long arch of the foot, and bones of the mid foot – improving the ability of the feet to absorb and transfer weight smoothly.

Try this!

Sit upright on a chair, legs hip width apart, feet flat on the floor. Feel the sitz bones reaching into the ground as the crown of the head lengthens toward the sky. Empty your legs, relaxing your thighs. Open the soles of your feet into the ground, feeling contact points on your heel, and under the ball of the first and fifth toes. Maintaining the contact points on the soles of the feet, visualize the sling much like a stirrup, supporting under the arch of the foot, with muscles pulling up on the inside and the outside of your calf.

Feel the balls of the feet gently spread out on the floor as the sling lifts a hanging heel off the ground. The thighs will continue to feel empty, and you may feel that as you lift the slings. When lowering the heel back to the floor, control its descent using the same sling muscles, and your connection through the feet into the ground. You may notice that when you move the ankle this way, the mid-foot feels more stable.

And then…

The trick now is to take this new movement strategy into weight bearing movement. Use the sling connection imagery to enhance the effectiveness of the classic calf raise exercise. Not only can this strengthen the feet and lower legs, it is also useful in aligning the legs as a whole. The inner part of the sling connects, via a myofascial track, up to the inner legs. Through this relationship, the whole inner leg is activated, and the inside of the knee tends to find support without having to focus specifically on the inner quadricep muscles for stability. As the whole inner leg is activated, in length, an intriguing and engaging influence is exerted on the body’s core via the continuation of that myofascial track into the pelvic floor and up into the trunk. You’ll find that as you finish your repetitions, your body may seem to balance itself more easily over your feet. Explore it as you walk, and you may find the hamstrings come into play more readily, and you’ll find a better feeling of being grounded to the earth.When working with the sling, you may even find that you are less likely to hyper-extend your knees!

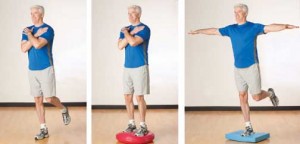

Now play with it in an unstable environment: step on a Bosu ball, or a rocker board, balance on one leg. Tune in to the motion of the heel, mid and forefoot under the talus. Feel what happens in your lower legs, knees and thighs. Check in with your hips and butt. At first you will likely feel very unstable – so you may want to start by holding onto something, or using a pair of ski poles to help you balance. If you can relax into the imbalance a little, find some length in your spine and then play with the sling – you’ll find that you can gradually develop a much better sense of balance in unstable situations. With practice and attention though, you’ll find that your strength and your balance will improve and you’ll be able to do this stuff more easily for longer periods of time. And then, in time, you’ll probably realize that you haven’t “turned your ankle” in a very long while!